Postcolonial Reclamations

From Al-Berka to Sidi Hussein

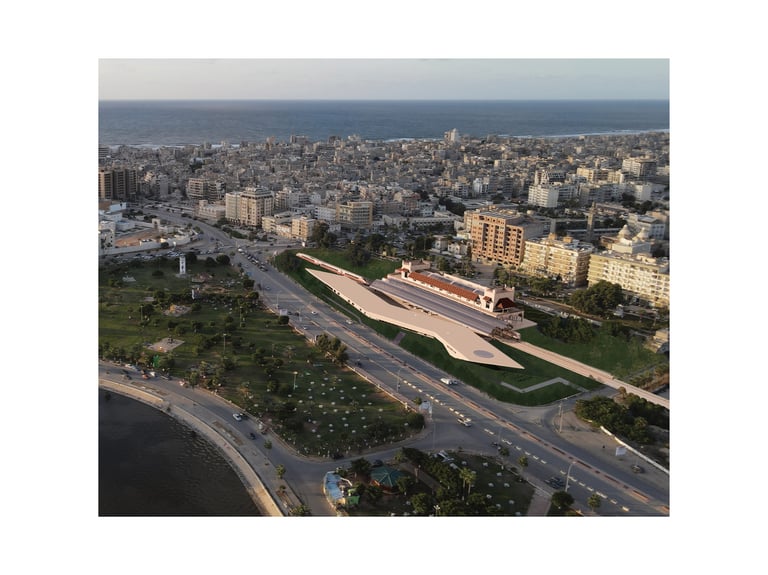

Barah Gallery, Benghazi 2025

The art and architecture exhibition "Postcolonial Reclamations: From Al-Berka to Sidi Hussein" calls for new ways to engage with both the architectural design process and the role of architecture in post-colonial geographies.

From 1911 to 1943, entire new districts were constructed by Italian authorities in Benghazi, Libya, redrawing the urban fabric to align with developments happening on the mainland, or at other times proposing totally new conceptions of exoticised Afro/Arab-Italian designs. The early 20th century hallmark of Modernism, reinforced concrete, became the norm for rationalist colonial architecture, while a pastiche of Islamic elements and Mediterranean porticos also lingered on in some public buildings.

The "reclamations" posited by the works on display are anchored in the methodology of the studio - Afro-Islamic means to conceive of architecture, with a focus on geometry, narrative, geology, landscape and materiality. But more than that, they are ways for local architects and students to engage with architectures that arrived on their doorstep from the outside world.

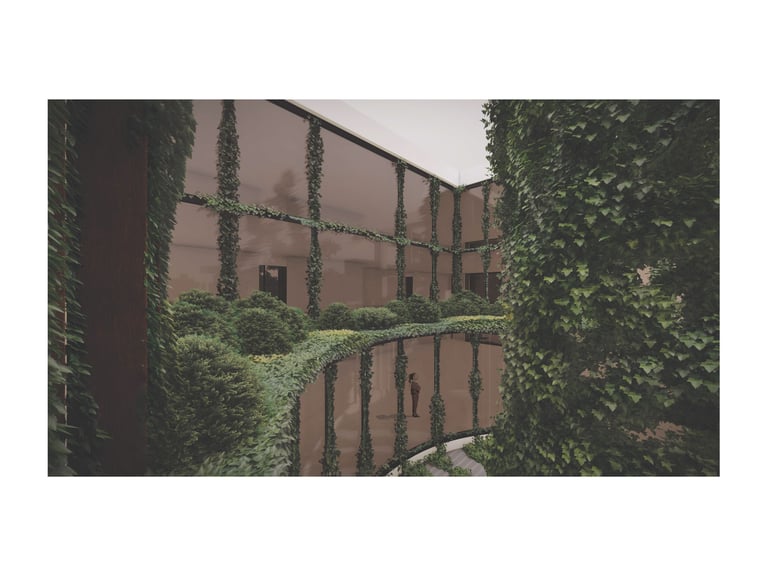

In the new educational building proposed by Islam El-Fallah for example, opposite a colonial school in El-Berka, local Ipomoea indica (an invasive ivy) takes over the facade as the years pass by. It highlights the evanescence of architecture over time against the forces of local nature. Likewise in the works of Raneem, Haya and Ahmed, landscape becomes a way to localise and engage with Italian and Ottoman urbanisms. In the proposals of Ali Al-Na'as and Saif Elhasi, the entire history of native Libyan materials - mud, palm and limestone - become a potent critique of Italian concrete.

All in all the works are a fascinating way to re-engage with colonial architecture at a time when Benghazi is witnessing major reconstruction works and questioning how to deal with its colonial legacy.

2025

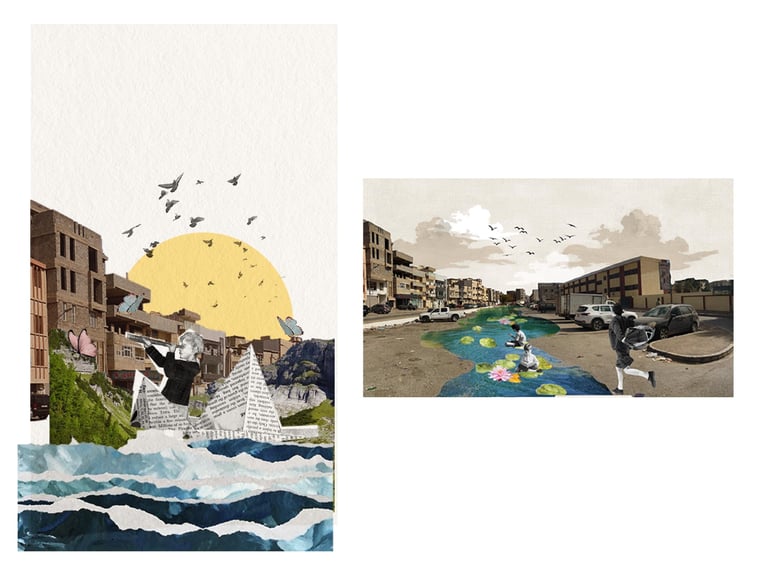

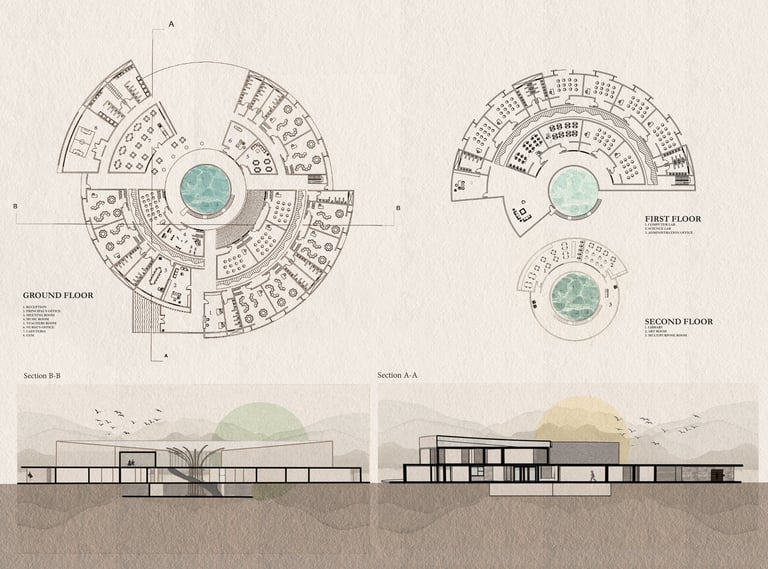

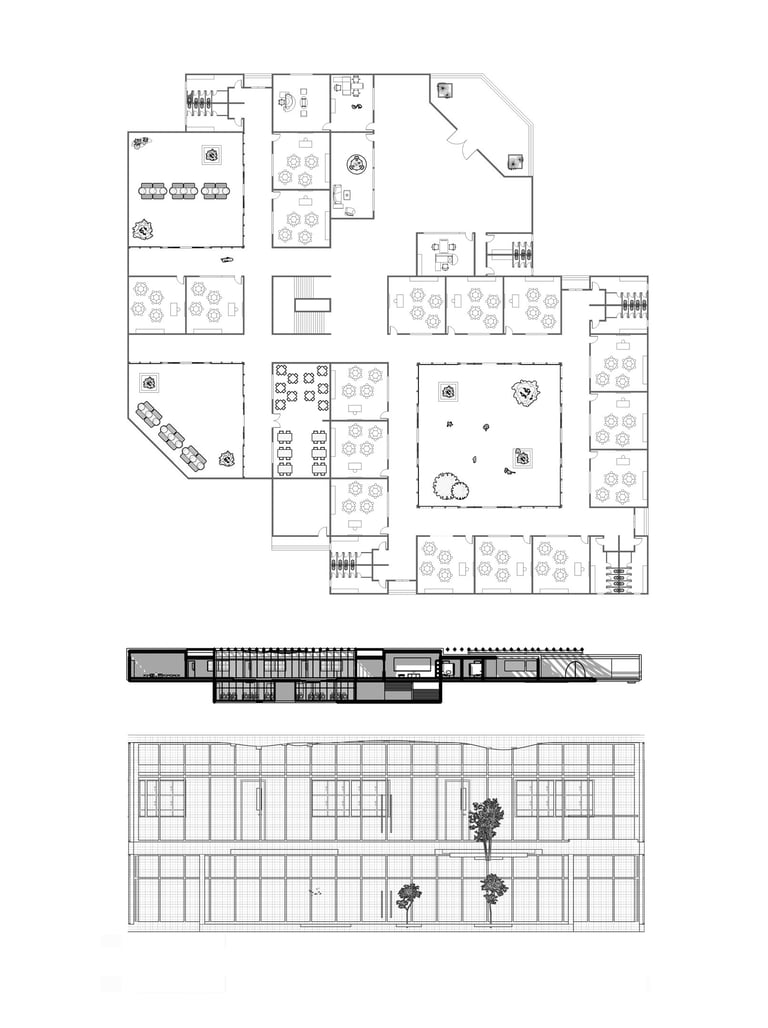

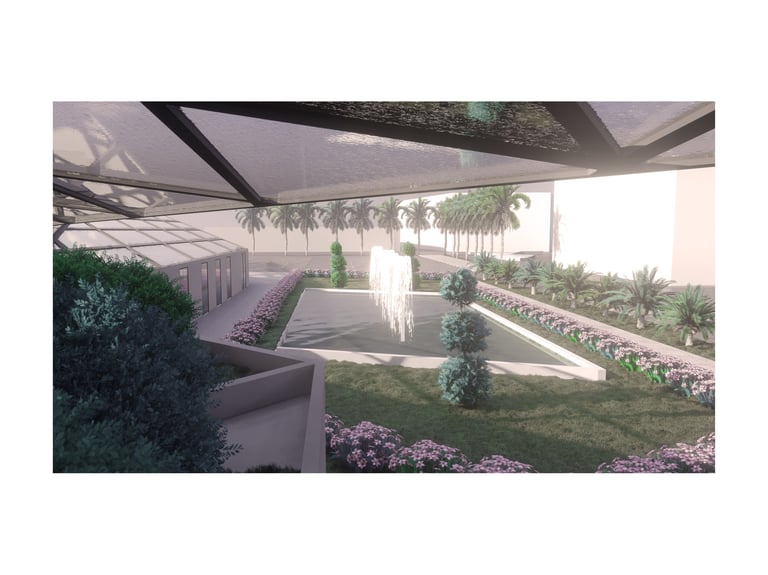

5.Raneem Benfadhl, The Secret Casket

At the crossroads of two Italian-era streets in Al-Berka, the Tariq bin Ziyad school is surrounded by a concrete landscape indifferent to water. In Maghrebi Islamic architecture however, water, air, and light are elemental forces. The Secret Casket reveals this sensibility through a hidden fountain, an echo of eastern Libya’s waterfalls, transforming water into a spectacle against the coldness of its surroundings.

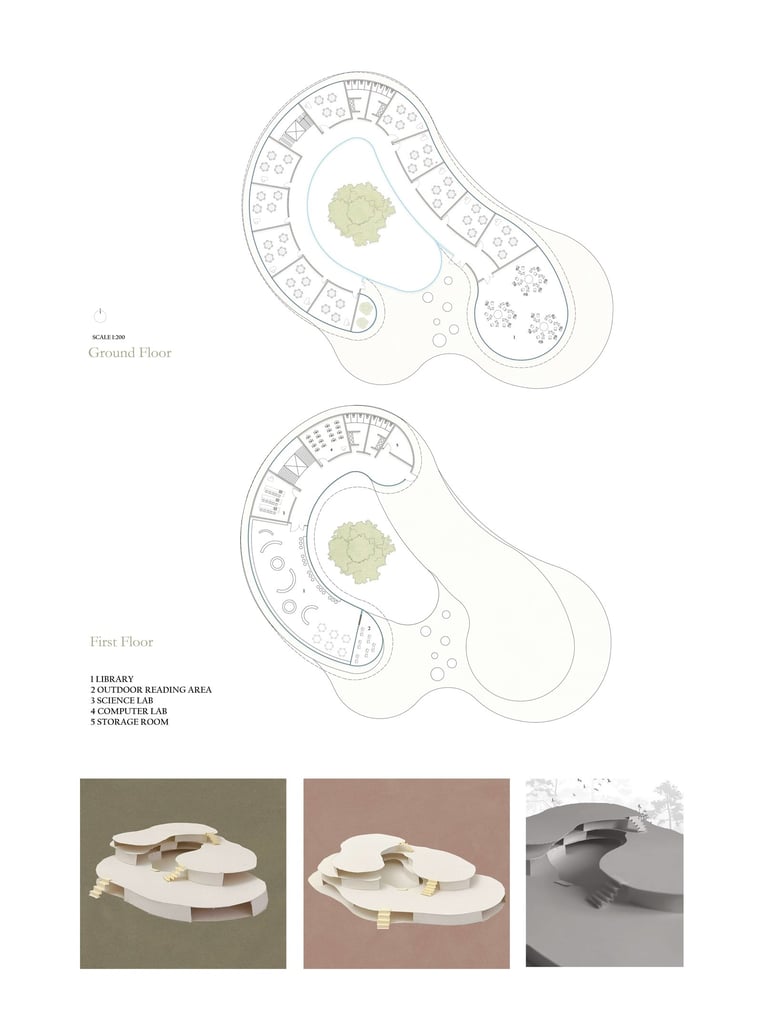

8.Suha Albarasi, Kaleidescope

Kaleidoscope is a school imagined through the eyes of a child. Inspired by the playful, colorful drawings of Sir Quentin Blake, its design, especially the central courtyard, embraces a child’s sense of scale and wonder. In doing so, it offers a quiet critique of Libya’s educational institutions and a challenge to the concrete monotony of Al-Berka.

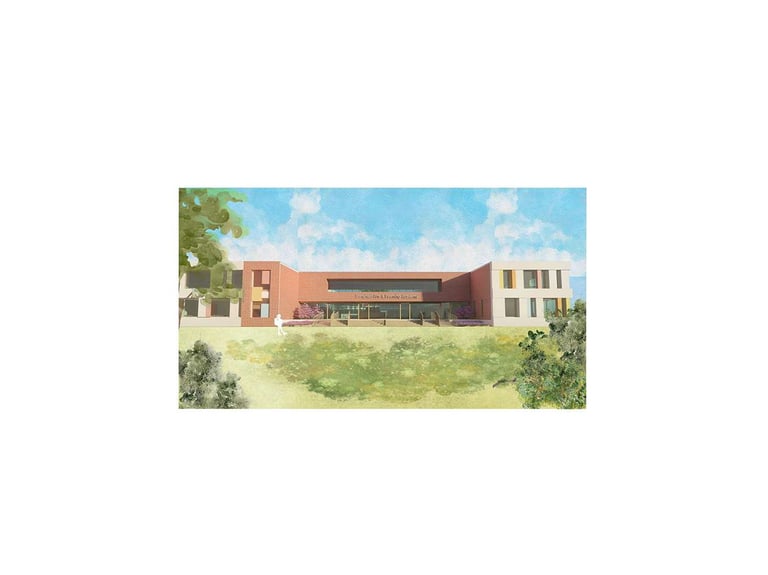

1.Islam Alfallah, The Protagonist

Time and botany are the two main protagonists of this new school in the colonial district of Al-Berka. A chance discovery of an invasive ivy (Ipomoea Indica) taking over the facades of some of the nearby buildings led to an investigation of the photographs of the American artist William Christenberry and the invasive kudzu in his native Alabama.

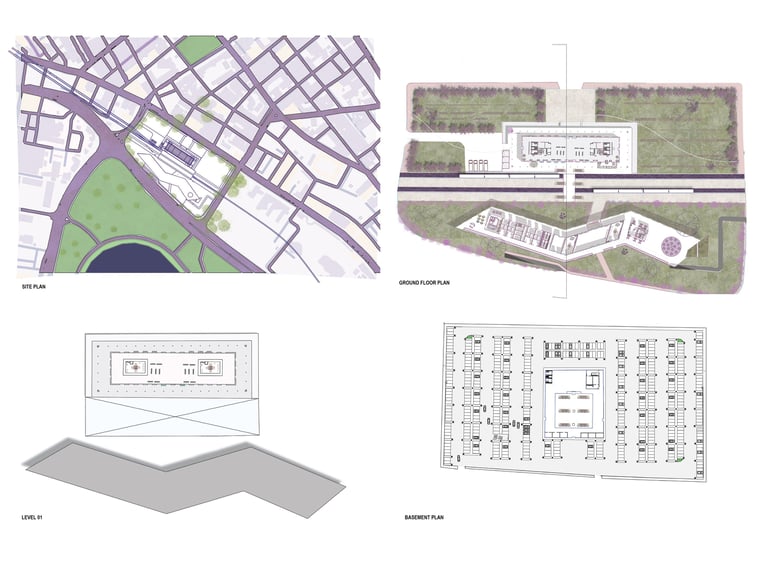

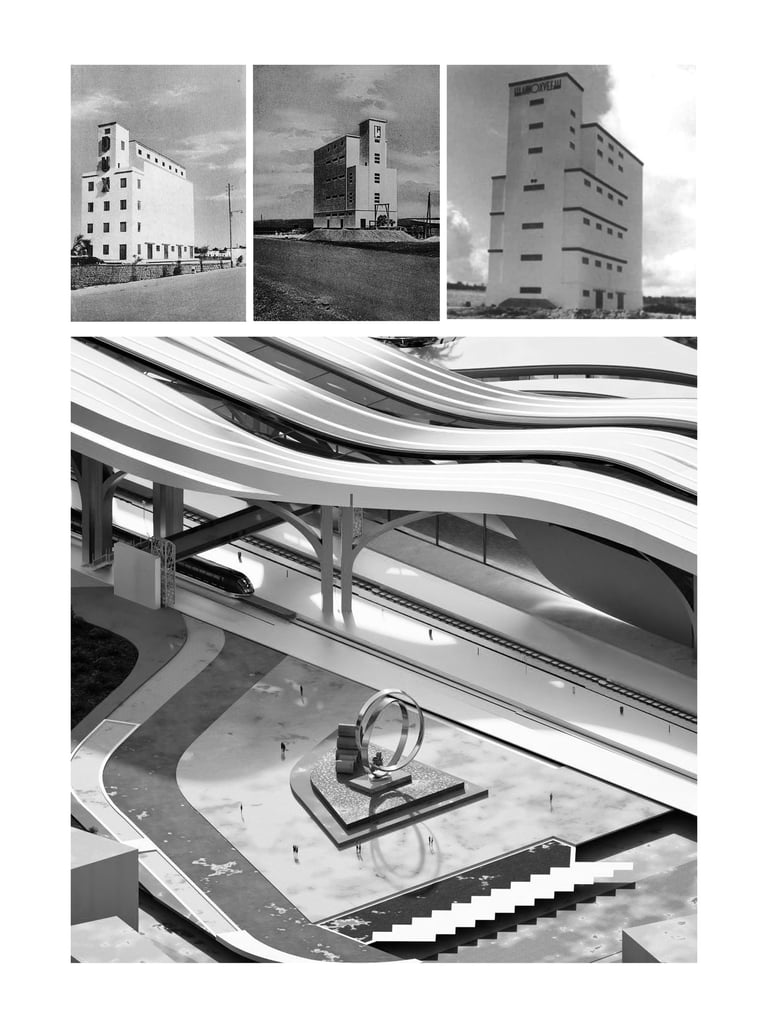

6.Rukayya Gargoum, La Stazione

This project calls for the rebuilding of some historic monuments "as is" whilst inventively reusing the interiors, in the same way Warsaw was rebuilt after the Second World War. Adjacent to the rebuilt Stazione train station in Central Benghazi is a deconstructed plan of the Italian building which speaks to the new drive of reconstruction in city.

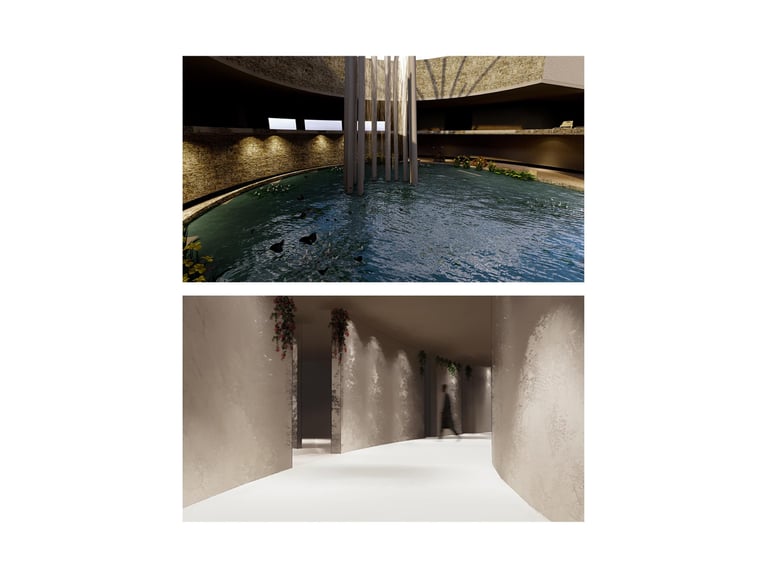

2.Saif Elhasi, Palm Station

When discussing Italian colonial buildings, the architectural theorist Mia Fuller mentions that 'a building's function was to confront the local population with Italian power'. Palm trees would have been considered a primitive building material, but in this new central station that sits on the site of the demolished Stazione, local building practices take centre stage.

3.Ali Alnaas, Mud School

Benghazi's "terra rosa" soil has a uniquely high iron content and is very rich in clay. A series of physical experiments with mud led to an investigation into various other soil types in Libya and how they might be used for a new school building based on their material properties, much like the work of Lina Ghotmeh and Diébédo Francis Kéré.

4.Mariam Alashebi, The Foundry

During the last months of 1937, the Benghazi area was struck by a persistent drought - the same year as the Granary Silo building was constructed in Sidi Hussein. Several testaments to Italian industries are still found inside the building today. The proposed train station down the road from the Silo building likewise celebrates Libya's home grown steel industry, and the recent announcement to construct the world's largest direct reduced iron (DRI) plant in Benghazi.

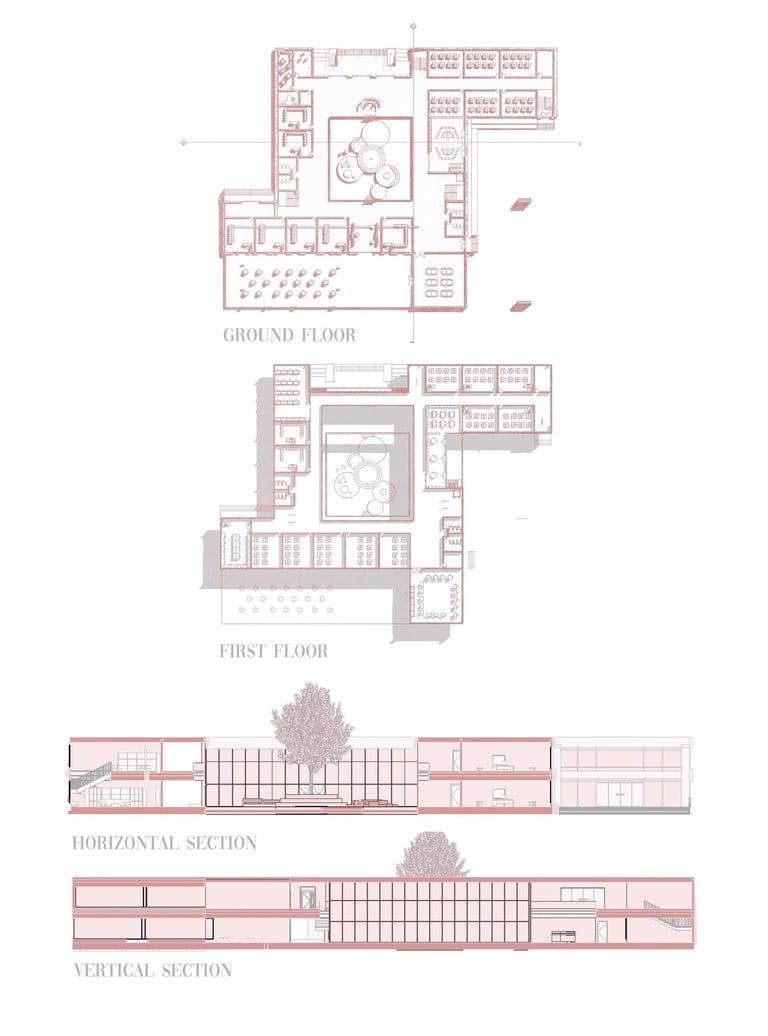

7.Haya Noureddin, The Organic School

Organic architecture is often misunderstood, but perhaps the definitions of the architect Frank Lloyd Wright are some of the most succinct. An interplay between the inside and out is one of the best ways for this school in Al-Berka to inspire healing in a post-war environment like Libya's.

9.Mabruka Mami, The Intimate School

Scale was a driving force for the design of the Intimate School, as well as the use of use of timber in many traditional architectures including Libya's. The reduced height central courtyard has a timber latticed roof which references traditional Benghazi roof construction, in the same way that the architecture of Shigeru Ban and Kengo Kuma became an Asian counterpoint to Western high tech glass and steel.

10.Ahmed Algazali, Monument

Benghazi is undergoing a construction frenzy and is looking fervently towards the future. Inspired by the architectural monuments of I.M. Pei, the train station Monument is an architectural statement piece which is carefully constructed and detailed to reflect a new era of architectural sophistication in the city. Like the Louvre extension in Paris, it boldly stands out amidst the historic architecture that surrounds it.

African Aperture

Multi Media Installation

The main work on display in the exhibition is African Aperture, a multi layered installation which is part historic artefact, part projection into the future. It is also a celebration of shared heritage. A group of disused windows from the Humaydha Apartments Complex built in the 1970s were salvaged from the ongoing reconstruction works in Al-Berka and re-appropriated as a work of art. They celebrate the Libyan, Egyptian and Turkish post-independence period of frenetic construction, and in particular the use of indigenous African mahogany for the windows.

The concept of a shared “Mediterranean” architectural language was primarily used by colonial authorities to “win over” local hearts, even if some architects famous for the style such as Florestano di Fausto (who designed extensively in Libya) were perhaps well intentioned.

In this installation, African raw materials, built locally and in the region frame and hover above colonial photographs – with proposals that sometimes restore Italian architecture and others that propose new readings – thus framing (literally and metaphorically) the architectural discourse on local terms.

Likewise the architecture model the frame holds is a reconstruction of the precise rail line of both the Ottoman and Italian colonial periods, but reimagined with several stops along the route, and a new central Stazione.